Economic vandalism

An interest piece written by Greg Smith, Head of Retail at Devon Funds.

March was challenging for markets, with investors having to deal with an ever-evolving trade situation. After a month-long pause, Donald Trump’s 25% tariffs on imports from Canada and Mexico came into effect early in the month, before exemptions were granted only a few days later. There was no such reprieve for China, which saw a doubling of tariffs to 20%. All three nations responded with retaliatory measures and tariffs of their own. The auto sector was also granted a temporary reprieve. Sector-specific tariffs were also implemented or proposed.

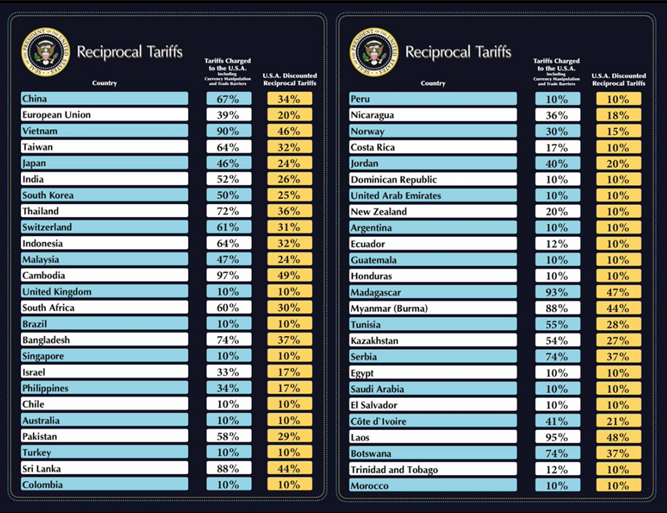

As we begin April, Trump has delivered a seismic shock to world trade with “reciprocal” tariffs on over 180 countries. Trump announced a “baseline” tariff of 10% and a sliding scale of tariffs, which his administration sees as representing half of what trading partners are charging the US – it is worth noting this includes VAT/GST, which does not single out the US. Notably, Canada and Mexico are not caught by the new arrangements, provided they comply with the USMCA agreement.

Source: The White House

Trump believes the tariffs will reduce the US deficit and pay off the national debt. Given that the US imported around US$3.3 trillion worth of goods in 2024, and the US national debt stands at nearly US$37 trillion, this is up for debate. So too is the claim of US$6-US$7 trillion worth of investment flowing into the US. The bigger question is the extent to which there is demand destruction, together with the broader impacts on the US economy, which is showing signs of some fatigue in places.

The S&P 500, after hitting record levels in February, fell 5.6% in March, while the Dow was 4.2% lower, and the Nasdaq tumbled 8.2%. For the first quarter, the Dow was down a relatively modest 1.3%. However, the S&P500 lost 4.6%, and the Nasdaq Composite dropped 10% - the worst quarterly performance for both benchmarks since 2022. Increasing trade uncertainties meanwhile saw gold surge to record levels above US$3,100 an ounce.

Trump’s tariff plans have seen April get off to an even more challenging start. The Dow Jones has fallen over 1500 points in back-to-back sessions for the first time ever. The Nasdaq is now in bear market territory, down 22% from its December record. The S&P 500 has hit an 11-month low and is down 17% since February’s record high. The broad benchmark has lost US$5 trillion in market value in two sessions.

When asked about the market reaction, President Trump (before heading to his club to play golf) said it was all “going very well” and that the market would ultimately “boom.” Oil prices, meanwhile, fell nearly 7% on the back of lower growth forecasts and as eight key OPEC+ members agreed to increase production. Amidst the global sell-off, the Kiwi and Australian markets held up relatively well.

It is worth pointing out that such severe market sell-offs, while not regular, have been seen before and have occurred throughout history. There was the GFC and, more recently, during the pandemic when panic set in with the arrival of Covid-19. The lesson from those shocks, and to paraphrase Kipling, is that it is all about “keeping one’s head” when others are losing theirs. The worst time to sell is when fear is ruling the market, as was seen during the severe but brief drop during the Covid meltdown, which preceded a multi-year bull market run.

Bond yields declined as investors also took the view that the Fed would be pressed to cut rates to combat the economic damage inflicted on the US via the tariffs. Recessionary risks have clearly risen, but even before Thursday’s announcement, growth forecasts had been tapered, and the term “stagflation” (stagnant growth with elevated inflation) had become more prevalent in investment circles.

One argument is that if tariff revenues are recycled back to tax cuts, then this could help support consumer demand. The reality, though, is that Americans will be paying much more for goods, which will propel short-term inflation, further complicating the picture for the Fed.

There is also the prospect that President Trump may cave to the pressure caused by a falling stock market, and as trade partners react in a different way to that which he intended. China has announced retaliatory tariffs of 34% on US products. A move away from globalisation could potentially drive a degree of unity outside of America (Europe is already talking about this), which could become increasingly isolated.

The other prospect is that should Trump remain steadfast, the decision to roll back tariffs may be forced upon him politically. It will be increasingly difficult to ignore the polls ahead of the midterms in November of next year. Trump will also likely be aware that history does repeat itself.

Estimates are that the average tariff in the US could increase by around 25% to circa 27%, which would be the highest in over 100 years. The Smoot-Hawley Tariff Act was signed in 1930 and raised U.S. tariffs on over 20,000 imported goods to record levels. The intention was to shield American businesses and the agricultural sector from foreign competition during the Great Depression, but it had several unintended consequences, including a significant reduction in international trade, retaliatory tariffs, and a more protracted downturn.

The architects of that tariff policy lost their seats, and the Republicans lost the 1932 presidential election, with President Hoover defeated by Democrat Franklin D. Roosevelt in a landslide. The negative effects ultimately saw a more cautious approach to protectionism and the eventual establishment of international trade agreements.

The question now, perhaps, is how long it takes for a rollback to be forced. Around 60% of American adults invest in the stock market, and the value of their investments and 401(k)s (retirement accounts) will be substantially impacted by the market sell-off. It would be safe to assume many Americans will be on the phone with their local Republican representatives to voice their displeasure, and this will ultimately feed back to the White House.

Republicans may already be looking to save their political capital, with a bipartisan bill coming out that intends to bring tariff power back to Congress. The bill requires Presidents to justify new tariffs and secure congressional approval within 60 days, otherwise, they would expire. Whether it gains traction in the Republican-controlled Congress remains to be seen.

Trump, meanwhile, has already contradicted White House aides by saying that he would be open to tariff talks with other countries if they offer something “phenomenal.” Is this the first baby step towards a gradual rollback of what was unveiled at the Rose Garden? Time will tell.

There has been a rush to make sense of the way in which tariff rates were calculated, given that even countries with which the US runs a trade surplus have been hit.

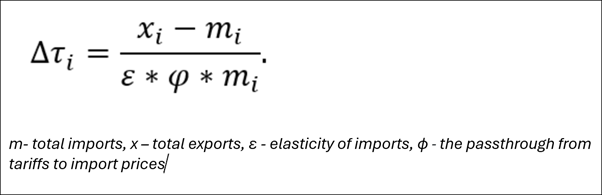

The White House provided some background to their tariff calculations (see here) and said that “reciprocal tariffs are calculated as the tariff rate necessary to balance bilateral trade deficits between the U.S. and each of its trading partners”. This calculation assumes that persistent trade deficits are due to a combination of tariff and non-tariff factors that prevent trade from balancing. The White House notes that the US has run persistent current account deficits for five decades, indicating that the core premise of most trade models is incorrect, and has come up with the following equation to rectify matters.

The simple maths, however, doesn’t add up in many respects, and certainly in terms of the “economic vandalism” that is effectively occurring as a result. Many of the tariffs are farcical and have been placed on “countries” with no people or territories (like Norfolk Island). Some of the higher tariffs are clearly miscalculated and placed on small countries like Lesotho (50% additional tariff) or Vietnam at 46%.

Markets have responded in kind with huge downward moves in names exposed to global trade, but also those correlated heavily with the US economy. Small-mid caps have been savaged – the Russell 2000 has entered a bear market (with a 20% fall from its peak).

Apple is a poster child for the malaise and the economic havoc being unleashed by Trump. China accounts for around 80% of Apple’s production capacity, and 90% of iPhones are assembled there. China will face a 34% tariff, but with the existing 20% rate, that brings the true tariff rate on Beijing to 54%. It would be an extremely arduous and costly process for Apple (which got an exemption from Trump last time around) to shift production to the US, and indeed, one it is not likely to do if the view is that there will be backtracking on the tariff policies at some point.

In the meantime, Americans will get to pay a lot more for their iPhones than they will for much more basic/staple items.

While China has been hit with heavy tariffs, only around 15% of its exports go to the US. It is conceivable that the Chinese economy holds up much better on a relative basis than the US in particular, and as Beijing continues to pull the domestic stimulus levers.

There is also the idea that goods previously shipped to the US will be diverted to other parts of the globe, including Asia, at lower prices. So, while the US is encountering an inflationary shock, there may be deflationary forces at work in Asia and elsewhere.

It will also be interesting to see to what extent goods are rerouted to other countries, with lower tariff rates, to have a new label put on them, before finding their war to the US. Are we on the cusp of “The Great Redirection”?

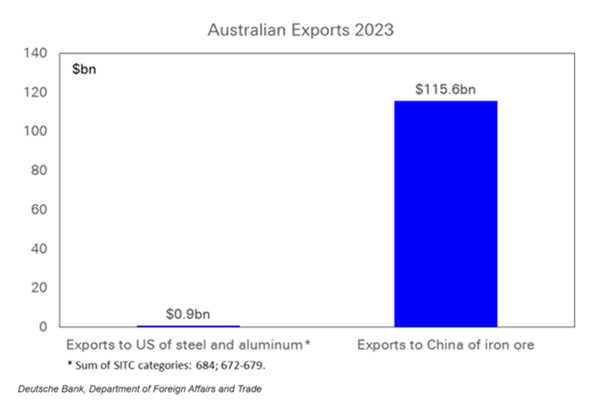

Some countries' fortunes are meanwhile more tied to those of China than the US. This includes both Australia and NZ.

The Australian market fell 3.4% last month despite a strong GDP outcome for the December quarter (the economy expanded 0.6%) and a soft inflation print. Australia has some names heavily reliant on the US for their sales (including the likes of Breville and Ansell), but generally, Asia carries more sway. As an example, the US accounts for only around 3% of BHP’s total revenues. The annual value of Australia's exports of steel and aluminium to the US is worth just three days of Australia's iron ore trade with China.

The Kiwi market was down 2.6% during the month and has held up relatively well amid the trade turmoil. The main name directly exposed to tariffs on the face of it is our biggest exporter, Fisher & Paykel Healthcare. However, it appears the company’s Mexican operations (which supply 60% of US sales) may be exempt as they are largely compliant with the USMCA agreement.

The direct impacts of the tariffs on NZ as a whole seem relatively contained. There are roughly $9 billion of annual exports to the US, so a 10% tariff is $900 million (a worst-case scenario), which is a very small percentage of GDP if this is a loss of export revenue (i.e. we absorb all the cost). This assumes we still export the same volume to the US. It also assumes there is no pass-through or any price increase in the US to mitigate the tariff.

In terms of the indirect impacts, that is harder to quantify. We are a small open trading economy, and our access to our second biggest export market has been altered (by way of increased costs), and our largest trading partner has been hit with 54% US import tariffs (China). Global trade, however, is still reasonably elastic, and one assumes that market forces will encourage more profitable and “easier” trade relationships – where that elasticity exists. So we can assume this will increase efforts to find and develop other markets for goods.

A seismic shock has been delivered to world trade, but the repositioning and redirection that occurs as a result could provide a silver lining for NZ, in addition to some potential deflationary tailwinds.

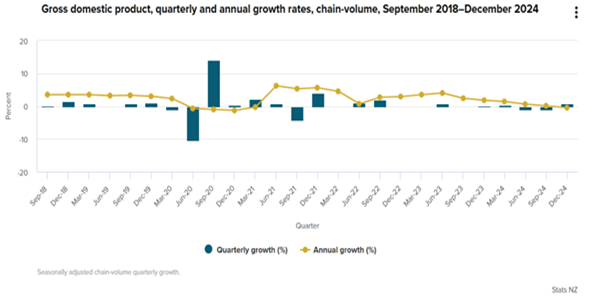

This would be welcome for a country that already had some good news during the month - the economy has staged a comeback and is out of a technical recession. Gross domestic product rose 0.7% in the December 2024 quarter, following a 1.1% contraction in the September 2024 quarter.

Higher spending by international visitors led to increased activity in tourism-related industries such as accommodation, restaurants and bars, transport, and vehicle hire. The largest fall was in construction (-3.1%). Cyclical industries may be amongst the last to respond to the easing we have had in the OCR and borrowing rates. Consumers, though, are already responding, it seems. Household consumption expenditure rose 0.1% this quarter. Also, something to celebrate is that GDP per capita rose 0.4% during the December 2024 quarter, its first rise in two years.

We have the RBNZ meeting this week, and while the economy is making progress (and the dairy sector is doing well), it is clearly crying out for more rate cuts. Central banks of late (the Fed, RBA, BoJ and BoE) have been adopting a “wait-and-see” approach before moving again, but the RBNZ has more colour than others did on the tariff policies of Trump. The central bank has a new acting head, and with inflation at the bottom of the target range (and potentially more deflationary forces on the way), a large cut seems appropriate. With the neutral rate of 3% and the OCR currently at 3.75%, there is just cause for a rate cut of at least 0.5%, given the seismic shock delivered to world trade last week.

While the next few weeks will undoubtedly be volatile, investors need to remember the recent lessons of Covid. Human ingenuity and responses should not be underestimated. Outside of the US, it is likely that we will see interest rates cut materially, and inflation will fall as goods are redirected away from the US. New trading blocks are likely to form, and there is a chance that the European market will open up. Australia and NZ are relatively well positioned. Ironically, the country that will be most negatively impacted is the US itself, and political pressure will come to bear on the Trump administration. Republicans will be shocked about the market reaction and will be conscious of their political futures.