Calming influences

An interest piece written by Greg Smith, Head of Retail at Devon Funds.

It was another volatile month for financial markets, but one that in the end produced a relatively benign outcome for investors. Trade developments were front and centre, with the angst around “Liberation Day” replaced by relief as Donald Trump announced a 90-day pause for trading partners to negotiate trade deals. Frictions with China also ebbed and flowed as tit-for-tat tariff increases gave way to olive branches, and exemptions on various categories of goods, and as the talk of the potential for negotiations continued to bubble away. After a hectic and volatile month, US markets staged a huge comeback – the S&P 500 was down 11% at one point, but closed April down just 0.7%, and just 9% off its record high, set in February. The tech sector surged back, with the Nasdaq closing the month 1.6% higher.

Donald Trump’s “Liberation Day” put markets on the back foot at the start of the month, but investor nerves were soothed in dramatic fashion as Trump announced a 90-day tariff pause and lowered the baseline on many countries to 10%. The S&P 500 has since recovered all the ground lost post-April 2. The benchmark recently rose for nine consecutive sessions, the longest winning streak in the last 20 years.

The Trump administration went on to claim that “200 deals” were in the pipeline, and that this was “always part of the plan.” The alternative theory is that Trump buckled to pressure from within his own party, his inner circle, trading partners, corporations, polls, and, possibly most significantly, the market meltdown.

Investors weren’t discerning the reasons either way, despite Trump raising the tariffs on imports from China to 145%. Following the pause announcement, the S&P 500 leapt 9.5% (the biggest one-day gain since 2008 and the third biggest in post-WWII history) in one session, and the Nasdaq soared 12% (the most significant rise since 2001). Apple, the world’s most valuable company, jumped 15%, for its best one-day gain since 2008.

Only Trump will know to what extent he caved in to the pressure, what his reaction was to the economic and market vandalism, or whether it was all part of a master plan. In any event, the market reaction was one of huge relief.

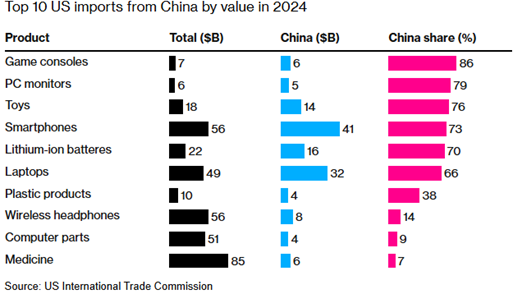

The ‘chicken run’ with China, meanwhile, continued. Trump said that he was raising the tariffs imposed on imports from China to 145%, beyond the initial 20% “fentanyl tariff.” China, meanwhile, increased the tariffs on US goods from 34% to 84%, and then to 125%. Publicly, Trump has since continued to extend the narrative that China has been “ripping off” the US for a long time, while there have been reports of behind-the-scenes phone calls to Beijing. In any event, the White House was the first to “blink” in providing exemptions covering almost US$390 billion in US imports and more than US$100 billion from China, or around 22% of its exports to the US.

Only around 15% of China’s exports go to the US, but the latter is hugely dependent on China for a host of products that can likely be made much cheaper in China.

As we enter May, time will tell how trade negotiations proceed with each country. However, recessionary risks have also been put on hold for now. Goldman Sachs (which saw a 65% chance of a recession in the next 12 months) and JPMorgan Chase are amongst those that have put their 2025 US recession calls on “pause.” Investors also pared back their expectations for Federal Reserve interest rate cuts.

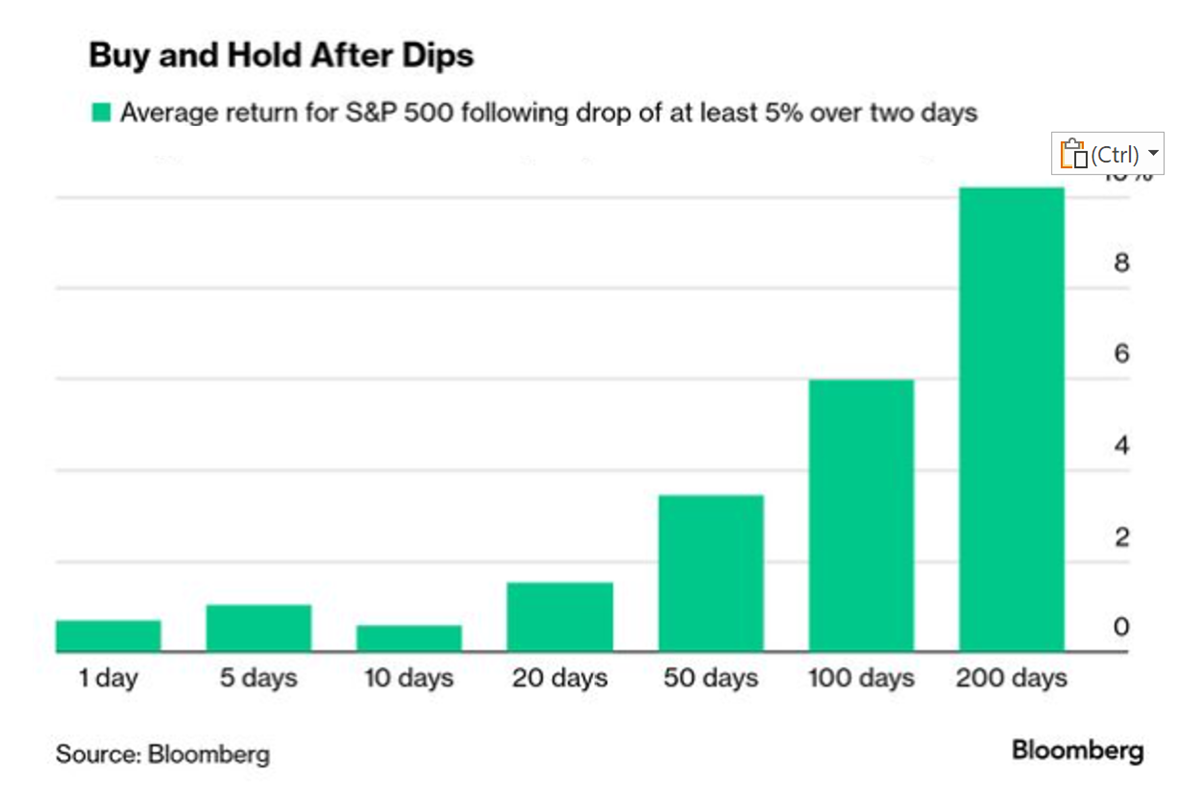

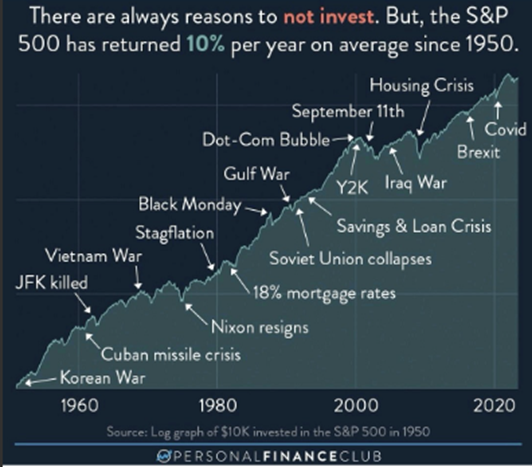

The reaction to the pause reinforces the comments made in our special report last month about the need for “cool heads” during the volatility that was seen in March and at the start of April. The tariff measures unveiled by Trump were always likely to represent the maximums for those countries willing to engage in negotiations and the worst-case scenarios.

Crises such as that which was effectively launched by the White House are not regular, but can and do happen throughout history. The performance of equities through each of these periods continues to provide valuable lessons and a reminder of the importance of holding one’s nerve.

There is still much uncertainty over how the trade situation will play out, but after the initial bluster, it is telling that the Trump administration has backtracked multiple times. “Pauses” have become commonplace, as have exemptions (including a complicated one for the auto sector), with the most notable one being that on smartphones and electronics - items that the US cannot make in the quantities needed any time soon.

All eyes are now on how things play out with China, and there is an argument that America needs China more than the other way around. This has been supported by several data points over the past month.

While the US economy is slowing down, China’s annual growth rate steadied at 5.4% in the first quarter, the strongest rate of expansion since the second quarter of 2023, and well above estimates for a slowdown to 5.1%. Industrial production, fixed asset investment, and retail sales all surged.

Little wonder that China is “not rushing to make nice” and is arguably in a stronger bargaining position. China is, though not immune to the tariffs, and authorities have downgraded the economic growth forecast for this year from 4% to 3.4%, but the country appears to be in a better relative position than the US. This is good news for countries that have China as a far larger customer, including NZ and Australia.

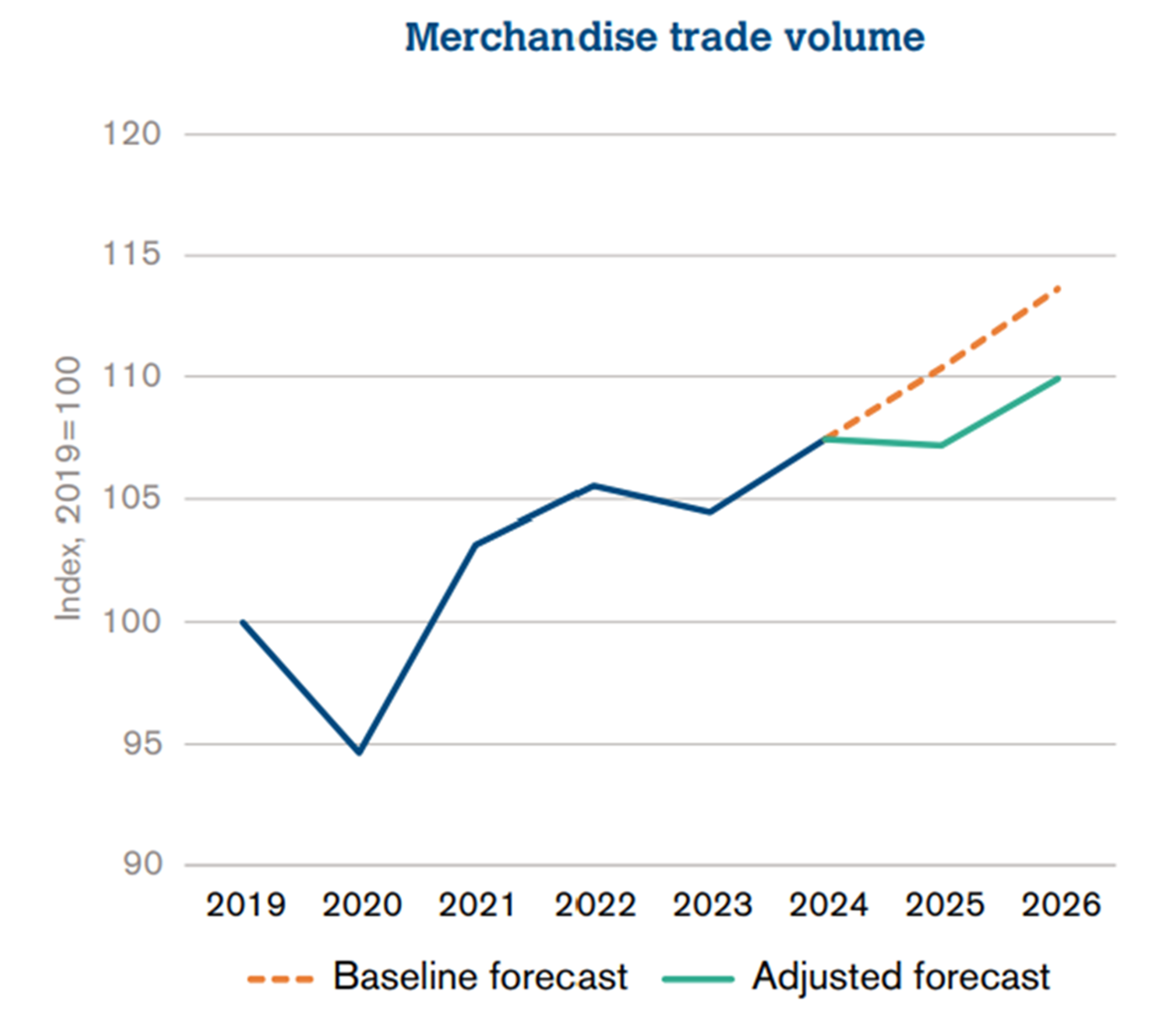

This is also while the current standoff is already delivering knock-on impacts. Cancelled sailings of freight vessels out of China have picked up, and the nation accounts for around 30% of all US containerised imports. The World Trade Organisation has cautioned that the outlook for global trade has “deteriorated sharply,” with impacts felt the most in North America.

Source: World Trade Organisation

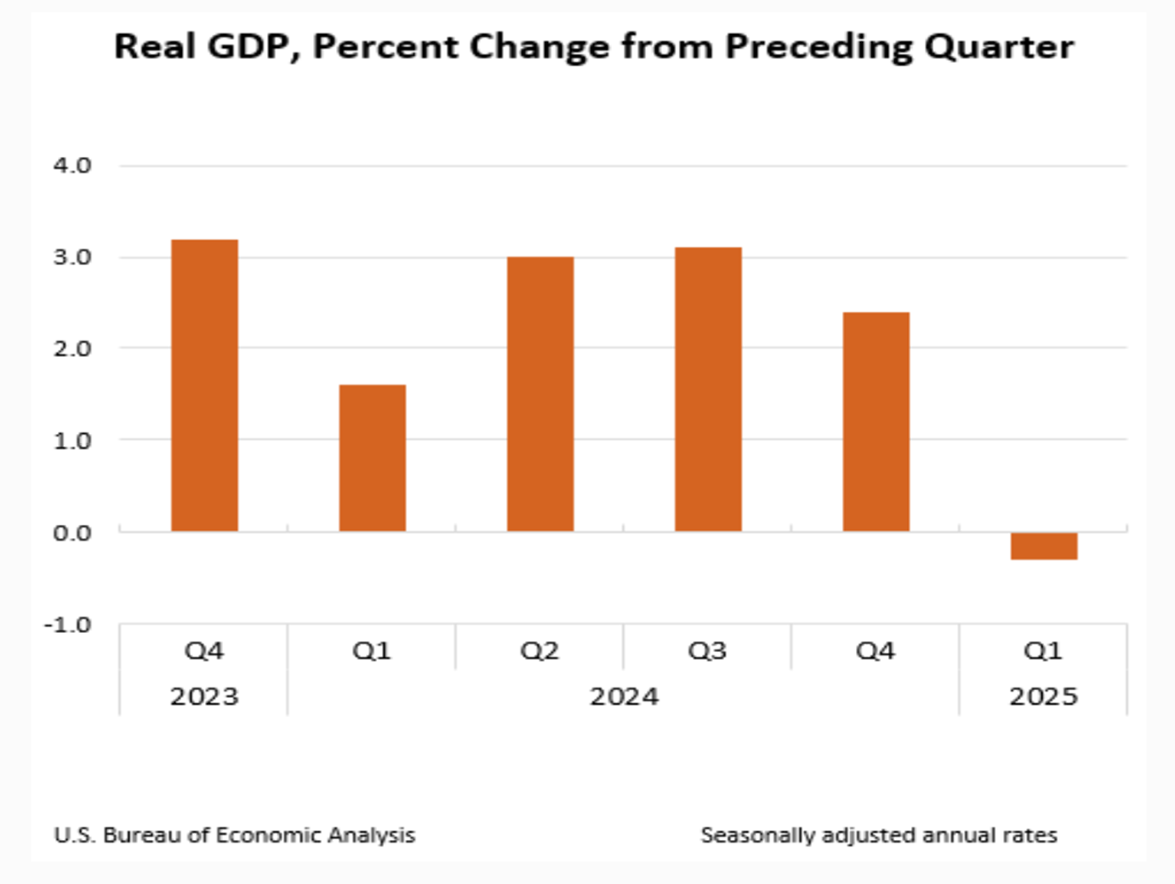

Also notable was that the US gross domestic product fell at a 0.3% annualised pace in the March quarter, driven by a surge in imports ahead of Trump’s tariffs deadline. It was the first quarter of negative growth since 2022, and expectations had recently been for a gain of 0.4%. Imports (which subtract from GDP) surged 41.3%, driven by a 50.9% increase in goods – the biggest surge (outside the pandemic) since 1974. Government spending also decreased (-5.1%) as Elon Musk’s DOGE team got into its work. These movements were partly offset by increases in investment, consumer spending (+1.8%), and exports.

US consumers are still spending, although it was the slowest quarterly gain since Q2 of 2023 and down from a 4% gain in the prior quarter. A separate report though, showed that spending was up 0.7% in March, higher than the 0.5% estimate.

The White House brushed off the headline GDP print, pointing to a surge in new domestic investment, highlighting “the best negative ever”, being a 22% increase in domestic investment, and 3% growth when stripping out the negative effects of the surge in imports because of the tariffs.

Time will tell if this narrative is correct, as it is conceivable that the import bump will reverse, and substantially so, into negative territory. Private investment could all continue to pick up as Trump claims that “companies are starting to move into the USA in record numbers.” Perhaps the bigger question will be how consumers (and the Fed) react as inflation escalates.

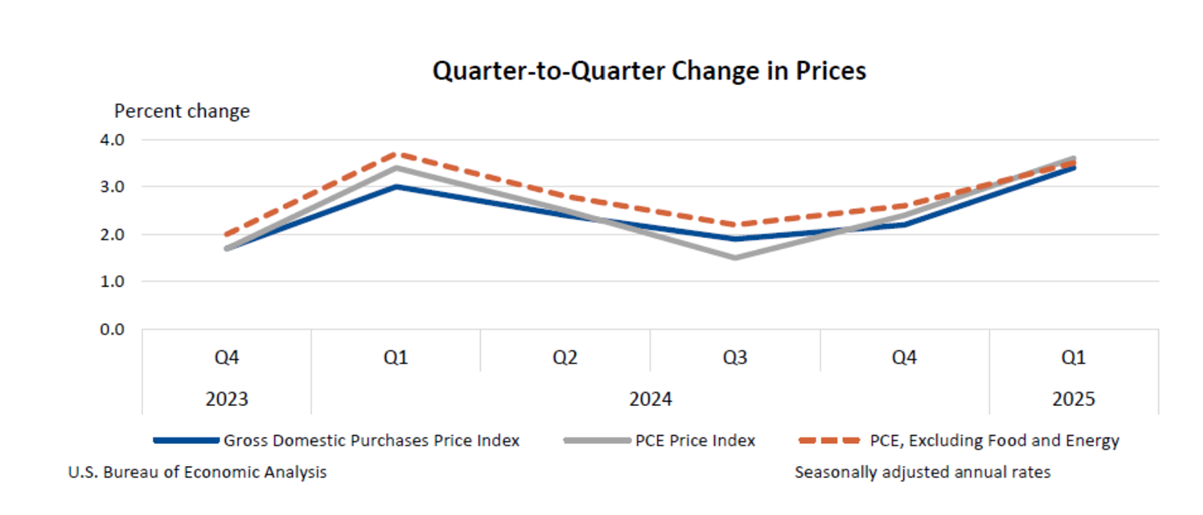

On that point, the Fed didn’t meet last month, but there was a release on the central bank’s preferred inflation gauge. The Personal Consumption Expenditures price index rose 3.6% for the quarter, up sharply from the 2.4% increase in Q4. Excluding food and energy, core PCE was up 3.5%.

Trump also apportioned blame on the Biden administration for price strength, claiming he brought inflation to the US at the ‘highest rates ever seen.’ Never let the facts get in the way of a good story. US inflation hit 29.8% in 1778 during the Revolutionary War, and 23.1% in 1920 post-World War I. Blaming Biden for US inflation (which peaked at 7%), which was driven by stimulus that was orchestrated globally in the response to the pandemic, seems a ’slight’ stretch in any case.

In any event, markets still are pricing in a rate cut at the June meeting (and none at the meeting in early May) and a total of four moves by the end of the year, on the notion that the Fed will prioritise economic growth over inflation.

Nonetheless, there is still a clear dilemma for the Fed. Chair Jerome Powell said during the month that the central bank’s focus was on preventing potential tariff-driven price hikes from triggering a more persistent rise in inflation. Fed officials, of course, have a base case to defend, having already claimed that tariffs will deliver a one-off inflation shock that will be transitory.

Powell also stated that the central bank may still find itself in a position where its “dual-mandate goals are in tension.” Powell was then the subject of Donald Trump’s ire for not bringing down rates soon enough. Comments from Trump that Powell was “in the firing line” did not sit well with investors, although these too were later backtracked on.

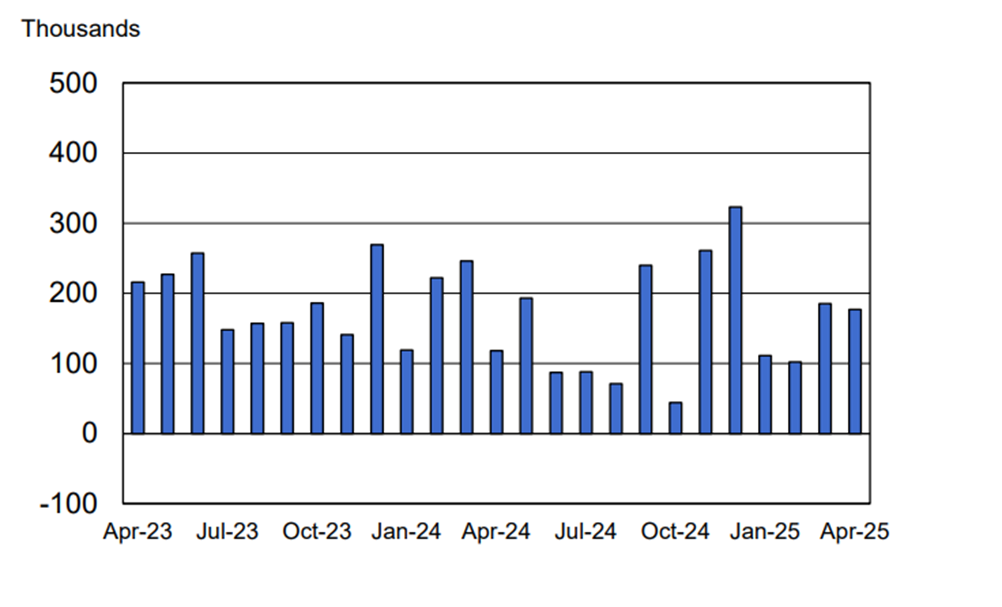

The complexities of the situation are compounded for a data-driven Fed, with different reports appearing to be telling different stories. One print showed that private hiring in April posted the smallest gain since July 2024. However, the Non-Farm Payrolls report in early May showed that the US economy created 177,000 jobs in April, around 40,000 more than expected. The unemployment rate held at 4.2%, with no sign “yet” of any negative impact from trade policy-induced uncertainty.

US Job creation

Source: US Bureau of Labor Statistics

Fair to say the situation is “fluid” on a number of fronts, and this has also come through in the US earnings season. The majority of companies reporting to date, including the financials and big tech, have beaten on earnings, but outlook statements have been less convincing and have highlighted the uncertainties that exist in abundance. Markets, however, appear to be taking the view that, just as was the case in March, the worst-case scenarios from here will not play out.

The performances of the Australian and New Zealand markets were quite different during the month. This highlighted the differing relationships of the indices to the trade war, and also the contrasting states of each economy and the situations the respective central banks find themselves in.

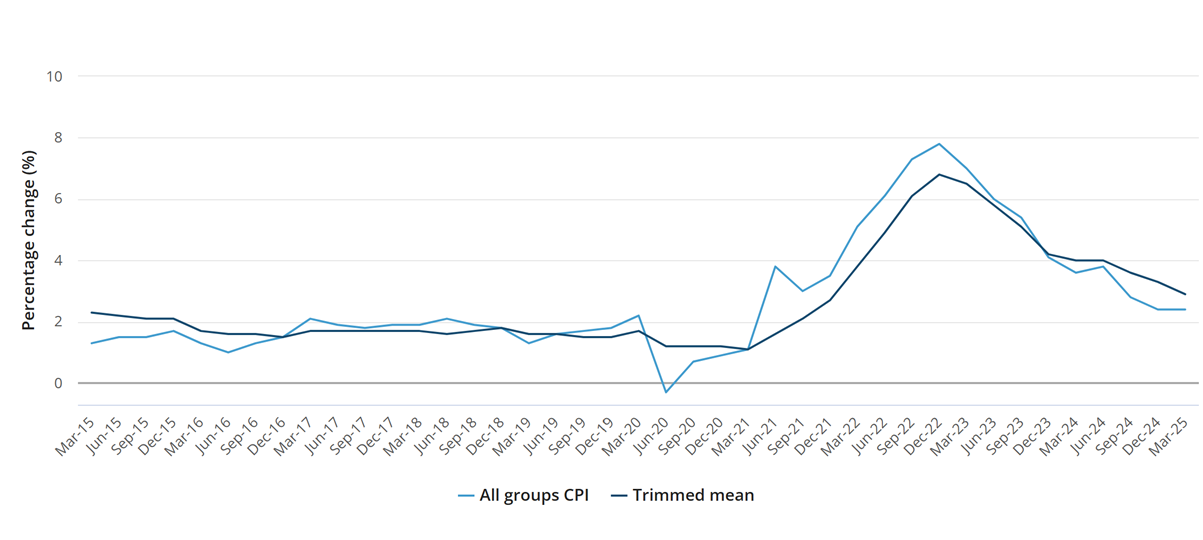

The Australian share market jumped 3.6% for the month to an 8-week high. The quarterly CPI came in a little higher than expected but fell back into the RBA’s target range for the first time since 2021, paving the way for another rate cut this month. This is also while the central bank will not have to worry about any dramatic changes to the local political landscape – Labour swept to a landslide victory in the Federal election in early May.

Australian CPI

Source: ABS

The Kiwi market closed down 3% for the month. Our market has not seen the same rebound as the likes of the US, Australia and other markets. That said, it didn’t fall as much either. The direct impacts of the tariffs for NZ as a whole seem relatively contained. There are roughly $9 billion of annual exports to the US, so a 10% tariff is $900 million (a worst-case scenario), which is a very small percentage of GDP. Red meat is the main export, and it remains to be seen whether this will continue to head into the US, plus ~10% or be diverted elsewhere. Our largest company, Fisher & Paykel Healthcare, exports the majority of its products to the US from Mexico, where production may ramp up, given that the exports appear to be compliant with the USMCA agreement and therefore exempt.

The NZX is seen as being more defensive and less directly exposed to China than the ASX, for example. We also do not have the tech giants of the US. Being more immune to trade developments than others, a key driver in the near term may be the prospect of further rate cuts by the RBNZ, to help our economy grind further out of recession.

The RBNZ delivered what was seen as a “dovish cut” of 25 basis points last month. Officials noted that trade frictions created “downside risks to the outlook for economic activity and inflation in New Zealand.” They added that “as the extent and effect of tariff policies become clearer, the Committee has scope to lower the OCR further as appropriate.”

The RBNZ meets later in May, and it is clear to us that (even though we may not get one) a cut of 0.50% is needed. The OCR is currently 3.5%. Notwithstanding the uncertainties from the tariff situation, the reality is that our economy is still only crawling out of a recession, and the neutral OCR is likely around 2.75%, if not lower.

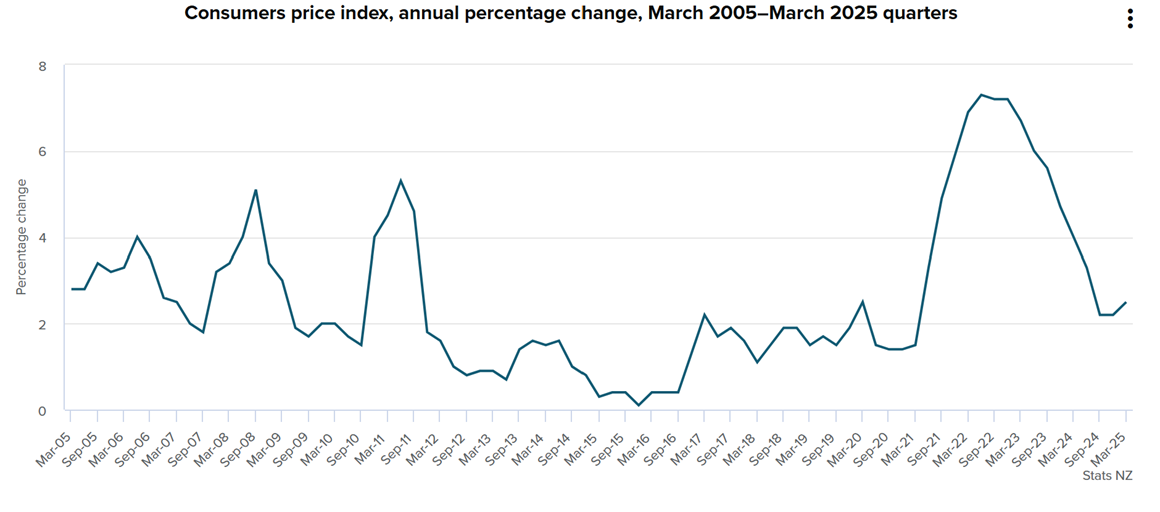

The quarterly inflation print last month should not deter the RBNZ from further rate cuts. The CPI came in at 2.5% on an annual basis, up from 2.2% annually in the December quarter, but within the RBNZ’s target band of 1 to 3% for the third consecutive quarter. There remains the prospect of further deflationary drivers as China diverts products away from the US at cheaper prices. In the scenario where countries are all cutting tariffs, there will be further deflationary forces at work. Inflation is already at the bottom of the central bank’s target. We have also had another deflationary shock – oil prices are down over 20% since the start of April.

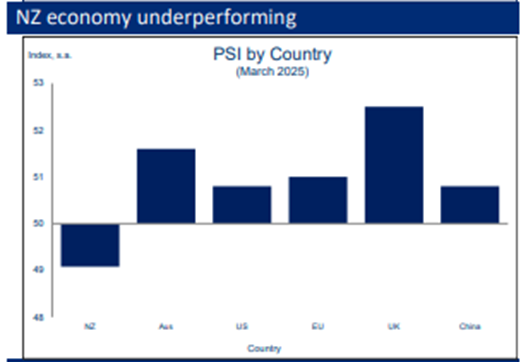

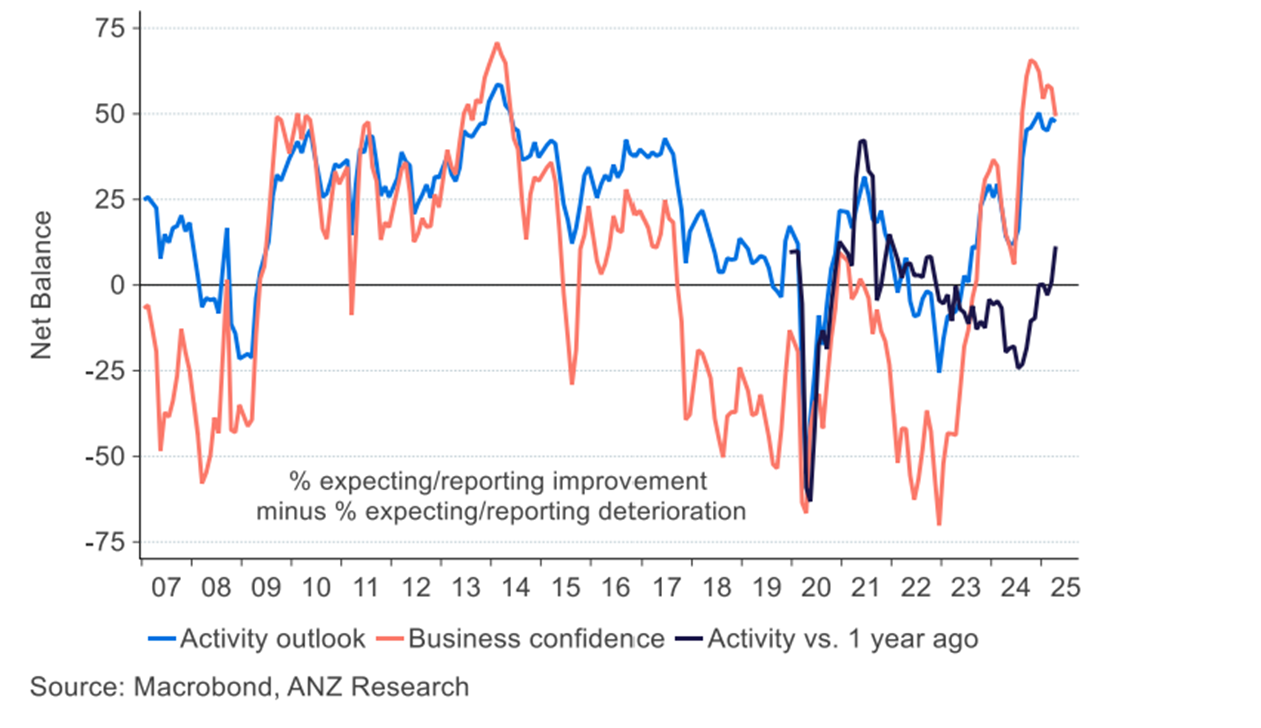

Economic confidence, by many metrics, is very low in historical terms. Dairy and tourism are doing well, but pretty much every other sector is struggling. Manufacturing has improved, but from a depressed base and the services sector is not exactly pumping (we are one of the few countries where it is in contraction).

Employment is 1.5% lower than a year ago, and unemployment is rising. The NZ Institute of Economic Research’s Quarterly Survey of Business Opinion showed that a net 17% of firms reduced staff in the March quarter. Firms are planning to reduce investment in buildings, plant and machinery. Cost pressures remain (the weak currency will be a factor), but the proportion of firms that are raising prices is at historic lows. The currency aside, inflationary pressures are continuing to ease against a backdrop of falling capacity pressures. Any green shoots in the business sector appear to be wilting.

We will hear more about what Kiwi corporates make of the economy and trade situation as the reporting season gets underway later this month. It could well be domestic factors, however, that determine how long it is before our market plays catch-up with others, and we see a re-rating of some high-quality names which continue to present good value.